October 2006

Why Worry? Why Not?

by Annie Fox, M.Ed

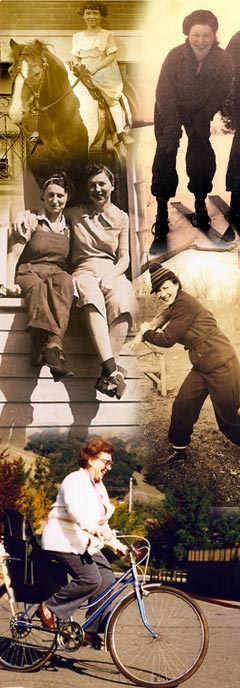

My mom grew up in New York City in the ’20s and early ’30s. The youngest of four spirited sisters, she loved competition and she delighted in challenges. I’ve got photos of her on horseback, perched on window ledges, skiing, and playing all kinds of sports. At 16 she passed a rigorous Red Cross Senior Lifesaving test. At 17, one of her first jobs out of high school was working for legendary women’s reproductive rights activist Margaret Sanger. And much later, faced with Lou Gehrig’s Disease, my mom continued living her life with courage and a sense of humor that inspired her family and friends.

While

she unflinchingly dealt with anything she encountered in the real world, including widowhood and single parenting,

she was often unglued by catastrophes that existed only in her imagination. No my mom was not psychotic, but she

was a worrier. I don’t say that out of any disrespect to her memory. I say it with the deepest

compassion because I know how much suffering her worrying caused her.

While

she unflinchingly dealt with anything she encountered in the real world, including widowhood and single parenting,

she was often unglued by catastrophes that existed only in her imagination. No my mom was not psychotic, but she

was a worrier. I don’t say that out of any disrespect to her memory. I say it with the deepest

compassion because I know how much suffering her worrying caused her.

As 21st century parents, and as the adult children of our own aging parents, we’ve got valid stuff to worry about. If worrying is going to move you to take action for change then that’s a good thing. But what about the involuntary, cyclical fretting that leaves you pretty much paralyzed? How many of us wallow in that from time to time? (I’m raising my hand here because as Dr. Phil often says, “You can’t change what you don’t acknowledge.”) So we worry, even though we know that it has no impact on anything except our stress levels and our mental and physical well-being. You know it’s futile and unhealthy, but what can you do when your imagination fills your mental movie screen with disturbing scenes? You never bought a ticket for this scary and irrational show. Watching it makes you feel powerless and fearful. You hate it and yet you don’t know how to pull the plug on the blasted projector.

Several weeks ago, as the fifth anniversary of the September 11 attacks approached, I spoke with a group of middle school students. Normally I talk to kids about real friends vs. the other kind and how stress gets in the way of making good choices. But since the media was raising questions like “Do you feel safer today than five years ago?”, I decided to ask the kids what they worried about.

Just so they understood where I was coming from, I gave them my definition of worrying:

Involuntary, out of control thoughts based in fear of some imagined future event or situation.

I also told them, “You know it’s worrying when the spinning of your mental wheels keeps you from moving forward toward a goal or the resolution of a conflict.”

To further illustrate the point, I gave them an example: “Suppose my friend’s been acting weird to me. I text her about it but she doesn’t reply. After school I see her taking off in the other direction, like she’s trying to avoid me. At home I call her, but no answer. I spend the whole evening worrying about what might happen tomorrow, imagining what she’ll say, how I’ll feel, how my other friends will play a role in the unfolding drama. I don’t feel like eating dinner. I have trouble focusing on my homework. When my dad asks me why I’m in a bad mood, I yell at him and pretend I don’t know what he’s talking about. Later, I’m still worrying about my friend and have trouble falling asleep.”

mental movie screen with disturbing scenes?

I assumed all the kids had experienced this kind of worrying. I assumed that they didn’t enjoy it any more than I did. I assumed they’d appreciate some tools to help them ease their worried minds. I assumed wrong.

Many of the students told me that worrying was actually a good thing and they resented my assumption that they should learn to do it less! Here are some of the points they made during our discussion:

“But if I don’t worry about my homework or a test, then I won’t do well. I

NEED to worry otherwise I won’t study. So worrying is a good thing.” (Does this child keep the negative

consequence of not doing well in mind as a motivator?)

“But if I don’t worry about my homework or a test, then I won’t do well. I

NEED to worry otherwise I won’t study. So worrying is a good thing.” (Does this child keep the negative

consequence of not doing well in mind as a motivator?) - “If I didn’t worry I wouldn’t care. And it’s not a good thing not to care about people.” (Does this child believe the opposite of worry is a lack of compassion?)

- “If I worry I can keep the people I love safe. And me too.” (Is this akin to my own air travel coping strategy: “I worry therefore the plane won’t crash.”)

- “Worrying is good because it prepares you for bad things. Like if I’m worried that my dog will die and then he does, well, I won’t be so sad when it happens.” (Does this child believe that worrying prepares and protects you from life’s emotional upheavals?)

- “Worrying makes life interesting. Without worrying everything would be really boring.” (Is this child confused about the difference between excitement, joy of discovery, anticipation and “out of control thoughts based in fear”?)

- “It’s impossible NOT to worry! Don’t you worry, Annie?” To which I answered, “Sure I do. Sometimes. But I’m learning to do it less and less.” I think this child believed I was lying and that no one could “learn” not to worry… not even for a little while.

These were all smart, articulate, and thoughtful kids. They sincerely believed that worrying can be a protective

act and can make life interesting. They seemed determined not to give it up. But when I asked if they’d ever

been kept awake by worrying, 80% of them instantly raised their hands. And when I followed up with “And

during those times, would it be a good thing to know how to turn off your worrying mind so you can relax and peacefully

drift off to asleep?” Yes, they all agreed that would be great, even though they didn’t believe it was

possible.

These were all smart, articulate, and thoughtful kids. They sincerely believed that worrying can be a protective

act and can make life interesting. They seemed determined not to give it up. But when I asked if they’d ever

been kept awake by worrying, 80% of them instantly raised their hands. And when I followed up with “And

during those times, would it be a good thing to know how to turn off your worrying mind so you can relax and peacefully

drift off to asleep?” Yes, they all agreed that would be great, even though they didn’t believe it was

possible.

Needless to say, we came to no conclusions, but it was in a thought-provoking discussion. I invite you to strike up a similar conversation in your family. Find out what your kids worry about. Be honest about how worrying affects you. Work together to come up with some ideas of how to ease each other’s worries. Being tuned into our kids’ moods puts us in a proactive place to help them. So does checking in with them on a regular basis (with the intention of support rather than being intrusive). Those two practices plus their knowing that you’re fully available when they choose to talk are top priorities for any effective parent during these worrisome times.

Be happy. Don’t worry.

In friendship,

Annie